Lisa Rose-Rodriguez

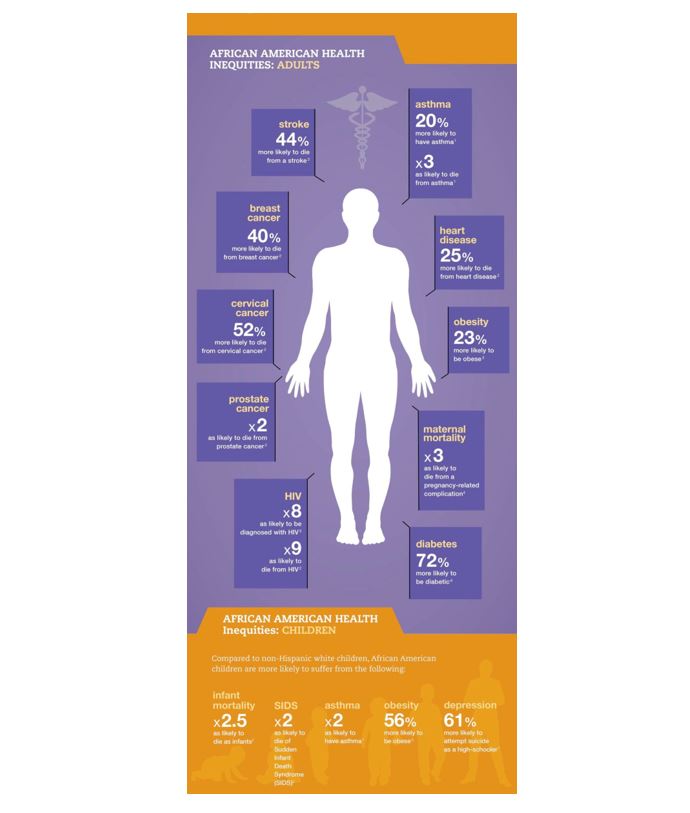

Healthcare disparities and inequities experienced by African-Americans are widely reported in both the local and national news. While healthcare inequities include obvious examples like diabetes, pregnancy is also one.

From the online article Exploring African American’s High Maternal and Infant Death Rate, we learn that per 100,000 births African-American women have a rate 0f 43.5 maternal deaths per 100,00 live births, compared to the rate of all US women, which is 14 per 100,00 in all other groups. this is called the maternal mortality rate.

Comparing this to developing countries is a fallacy, but looking at white and Latino women in America means there is a significant health care disparity.

As Epidemiologists we look for patterns of illness in populations. The pandemic of COVID-19 makes predicting and getting in front of illnesses very important. While all the risk factors associated with this healthcare disparity are not fully known in relationship to the virus, many researchers and healthcare professionals are willing to call systemic or institutional racism a definite factor.

The effects of racism in healthcare are: age-at-onset, being a pregnant teen, high school dropout rate and education level of the mother and grandmother. Consequently, a pregnant Black woman during this pandemic has increased risk factors. Infectious disease can easily impact the state of maternal health.

Obstetrics-Gynecologist doctors know that there are several factors that cause teratogenic effects. Teratogens, refer to substances or chemicals which can cause developmental abnormalities. The presence of infectious diseases in pregnant women has also historically resulted in abnormalities. The applicable formula we are discussing here is the one that increases negative birth outcomes within the realm of maternal-infant health for African-American women and their babies.

During the on-going COVID-19 pandemic reports continue to expose the fact that African-Americans are experiencing more sickness and death than whites during this national crisis. This is not an exception; this is already the history within the community before the pandemic. Black people are dying from illnesses that white people are cured from. Analyzing the background naturally a question emerges; what does this mean for a pregnant Black teen-ager who lives in a house where both of her parents have tested for COVID-19? Isolation and quarantine are the preventative strategies that come to mind, but what is actually known at this juncture about COVID-19 and pregnancy in America?

The Mayo Clinic writes: “The overall risk of COVID-19 to pregnant women is low. However, pregnancy increases the risk for severe illness with COVID-19. Pregnant women who have COVID-19 appear more likely to develop respiratory complications requiring intensive care than women who aren’t pregnant, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnant women are also more likely to be placed on a ventilator. In addition, pregnant women who are Black or Hispanic appear to be disproportionately affected by infection with the COVID-19 virus.”

The article continues by describing the unknowns. Children who have been born during the pandemic of 2020 are less than a year old. Currently, it is unknown if these babies, who are still developing, will have physical or mental deformities based on the exposure to the disease in the womb.

The solution for reducing the cases of infant mortality and maternal deaths in African-Americans is a multipronged strategy. First within the context of a pandemic, health providers must work hard to drive home prevention methods for pregnant women. In today’s world, physicians must be brave enough to admit that there are still unknowns, such as whether or not the baby will have developmental delays as a toddler.

Knowing when and how you conceived the child will also be helpful in managing the risks of childbirth. Abstaining from alcohol and cigarettes during pregnancy has been one prevention that has been practiced for decades. Soon to be parents should also know their AIDS, Hepatitis and COVID-19 status.

Recent urban unrest has shed light on the thinly veiled suffering of African-Americans. These two seemingly unrelated events have co-occurred and blossomed into an increase in public awareness. Hopefully policy and practice that improves health care outcomes for African-Americans is coming soon. One day as efforts increase, our disparities will decrease and our second-class citizenship as it relates to our health will be replaced with healthy numbers that closely resemble the larger population.

As a Public Health professional, I believe that the general public can take steps to reduce disease transmission. I urge people to continue to practice preventative measures. Remember that social distancing helps control the spread of virus particles that lodge in the respiratory tract. Singing, laughing, coughing and talking are all ways that the virus is spread.

This holiday season remember, wearing masks and washing hands is a gift to others.

Lisa Rose-Rodriguez received her Epidemiology training at the University of Connecticut Health Center.

Funded by the Solutions Journalism Network and Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative – NEO SOJO.